The plaintiff alleged that the defendant infringed on his pen and ink depiction of two dolphins crossing underwater. Applying the objective extrinsic test for substantial similarity, the panel held that the only area of commonality between the parties’ works was an element first found in nature, expressing ideas that nature has already expressed for all, a court need not permit the case to go to a trier of fact.

Plaintiff Peter A. Folkens (“Folkens”) alleged that Defendant Robert T. Wyland (“Wyland”) infringed on his pen and ink depiction of two dolphins crossing underwater. Folkens contends that Wyland’s depiction of an underwater scene infringes on his drawing by copying the crossing dolphins, and that the similar element of two dolphins crossing underwater is protectable under copyright law, entitling him to proceed to trial on the issue of whether Wyland’s painting violates his copyright.

The panel considered whether two dolphins crossing underwater is a protectable element under the objective standard of court’s extrinsic test for substantial similarity. The court held that the depiction of two dolphins crossing underwater in this case is an idea that is found first in nature and is not a protectable element. The court noted that a collection of unprotectable elements – pose, attitude, gesture, muscle structure, facial expression, coat, and texture – may earn “thin copyright” protection that extends to situations where many parts of the work are present in another work. But not in this case.

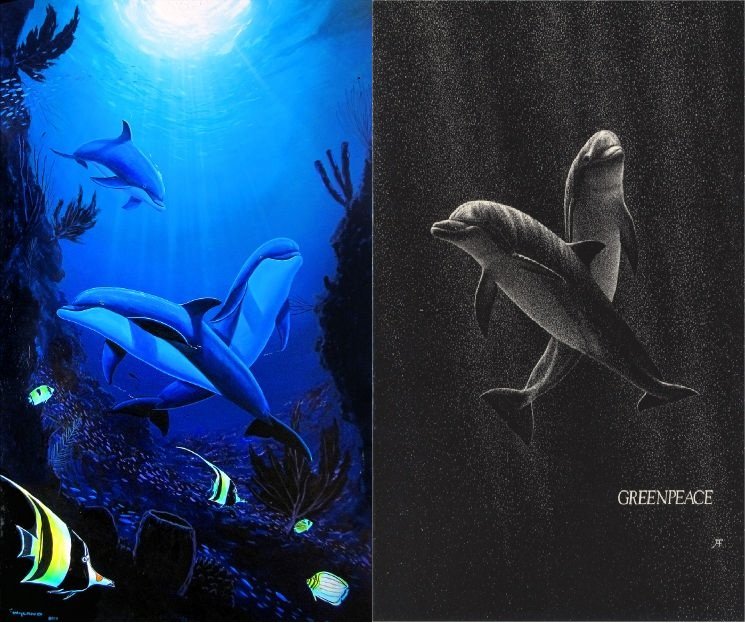

Folkens is the author and copyright owner of a pen and ink illustration titled “Two Tursiops Truncatus” also known as “Two Dolphins,” which he created in 1979. Two Dolphins is a black and white depiction of two dolphins crossing each other, one swimming vertically and the other swimming horizontally. No other subjects appear in the pen and ink illustration. The illustration has at least one copyright registration, VA 31-890.

Folkens alleged that in 2011 Wyland created an unauthorized copy of Two Dolphins in a painting titled “Life in the Living Sea.” Wyland’s Life in the Living Sea painting is a color depiction of an underwater scene consisting of three dolphins, two of which are crossing, various fish, and aquatic plants. Folkens alleged that in total Defendants created enough prints to make $4,195,250 from sales of Life in the Living Sea.

Folkens further alleged that Defendants have created other unauthorized copies of Two Dolphins for use in advertising on the internet. Folkens alleged that Defendants currently display the infringing works at galleries around the country. Folkens stated that he found out about the infringement in October 2013, and that he informed Defendants about their infringing works on or about September 18, 2014. The lawsuit followed.

The district court granted summary judgment for Defendants after applying the Ninth Circuit’s extrinsic test of substantial similarity to assess whether the Defendants’ work infringed Folkens’s copyright. Copyright protection only extends to original works and the district court had to first dissect the works, Two Dolphins and Life in the Living Sea, to determine what elements were original and protectable, and what elements were unprotectable. Then, under the extrinsic test, the district court properly only compared the works’ protectable elements to determine if the works were substantially similar as measured by external, objective criteria.

The district court found that “the main similarity between Wyland’s ‘Life in the Living Sea’ and Folkens’s ‘Two Dolphins’ is two dolphins swimming underwater, with one swimming upright and the other crossing horizontally.” The district court concluded that “this idea of a dolphin swimming underwater is not a protectable element” because natural positioning and physiology are not protectable under Ninth Circuit precedent, citing Satava. The district court commented that “the cross-dolphin pose featured in both works results from dolphin physiology and behavior since dolphins are social animals, they live and travel in groups, and for these reasons, dolphins are commonly depicted swimming close together.”

The district court further found that Folkens had not identified any elements of his work that are not commonplace or dictated by the idea of two swimming dolphins. The district court concluded that no reasonable juror could find substantial similarity between the two works because the element of similarity between Two Dolphins and Life in the Living Sea was not a protectable element. The Folkens appealed.

Folkens conceded that the idea of dolphins swimming underwater is not protected, but argues that his unique expression of that idea is protected. Folkens contended that the dolphins here do not exhibit behavior shown in nature because the dolphins in the photos that Two Dolphins was based upon were posed by professional animal trainers in an enclosed environment. Folkens contended that Defendants offered no evidence that the crossing of two dolphins in this way occurs in nature, and that fact alone should have precluded summary judgment.

Defendants argued that the district court correctly concluded that scenes found in nature, such as dolphins crossing in the wild, are not protected by copyright laws and that there were no protectable elements that were similar based on the shared subject matter. Defendants further argued that Folkens’s reliance on the fact that the dolphins were posed is a red herring because animal trainers can pose animals to capture positions that naturally occur in the wild.

The parties do not dispute that Folkens owns a valid copyright, but instead focus on whether Wyland copied constituent elements of the work that are original. Because direct evidence of copying is often not available, a plaintiff can establish copying by showing (1) that the defendant had access to the plaintiff’s work and (2) that the two works are substantially similar. Defendants have not contested access to the works, but argued, among other things, that “as a matter of law, there is no substantial similarity” between Two Dolphins and Life in the Living Sea.

The court considered only the extrinsic test – an objective comparison of specific expressive elements focusing on articulable similarities between the two works. The extrinsic test considers only the protectable elements of a work. The parties agreed that the element of similarity is the two dolphins crossing. The key inquiry is whether the crossing dolphins are a protectable element. Folkens contended that his expression of two dolphins crossing is a protectable element, while Defendants argued, and the district court concluded, that it was a naturally occurring element and therefore not protectable under copyright law.

First, the fact that a pose can be achieved with the assistance of animal trainers does not in itself dictate whether the pose can be found in nature. For example, an animal trainer may be used to get a dog to sit still while a photograph is taken or a painting is done, but no one would argue that the position of a dog sitting was not an idea first expressed in nature. In that case, the trainer’s purpose was not to create a novel pose, but to induce the dog to hold that pose for a period of time. Similarly, here, the dolphin trainer got one dolphin to swim upwards while its photo was taken, and got another to swim horizontally while its picture was taken. Neither of these swimming postures was novel.

An artist may obtain a copyright by varying the background, lighting, perspective, animal pose, animal attitude, and animal coat and texture, but that will earn the artist only a narrow degree of copyright protection. There is no question that the other aspects of Two Dolphins and Life in the Living Sea, beyond the two dolphins crossing, are different – Life in the Living Sea is in color, includes a third dolphin, has different lighting, and includes several species of fish and marine plants.

The court concluded that a depiction of two dolphins crossing under sea, one in a vertical posture and the other in a horizontal posture, is an idea first expressed in nature and as such is within the common heritage of humankind. No artist may use copyright law to prevent others from depicting this ecological idea. Two Dolphins also represents dolphins swimming vertically and horizontally, ideas requiring no stretch of the average person’s imagination because dolphins do this in nature. The basic idea of copyright law is to protect unique expression, and thereby to encourage expression; it is not to give to the first artist showing what has been depicted by nature a monopoly power to bar others from depicting such a natural scene.

Folkens holds a thin copyright in his expression of the two dolphins in dark water, with ripples of light on one dolphin, in black and white, but that copyright is narrow. The protectable elements that form Folkens’s thin copyright in Two Dolphins are not substantially similar to Wyland’s crossing dolphins in Life in the Living Sea. Wyland’s dolphins are in color, do not show light ripples off the body of a dolphin, and the dolphins cross at different angles. Because the depictions of two dolphins crossing here share no similarities other than in their non-protectable elements of the dolphins crossing, the judgment of the district court has been affirmed.